While we were always a low-income family, after my father went to prison, we became destitute. My family moved to Peter Knoll Homes, a housing project in Newport Kentucky. These projects were built at the confluence of the Licking and Ohio Rivers and were prone to annual flooding. My mother received a meager child welfare allowance and food commodities to feed us. This was years before food stamps and commodities included foods like wheat and corn flours, butter, cheese, dried beans and canned meat. Our mother sold the cheese for extra cash, and we frequently went to bed hungry. She also spent most of the monies intended for clothing and her children’s other needs drinking in the local bars.

My mother resented and punished me for “breaking up our family.” Somehow, it was not my father’s fault for abusing me. It was my doing for reporting the abuse to the county child welfare worker. It was all my fault and my mother and older sister, Liz, reminded me frequently. A local boy who was dating my sister raped me. That was “my fault” too.

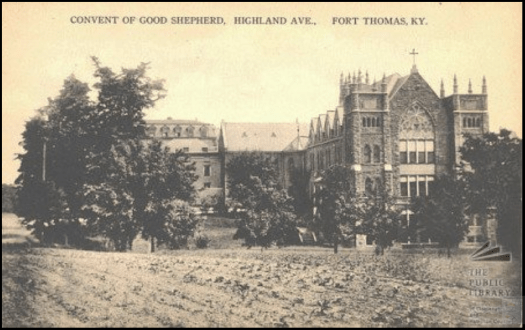

After years of chronic abuse, I suffered from what I now know was Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. I suffer to this day. I was timid, anxious, depressed, and my affect was flat. I lived in a state of isolated terror and frequent tachycardia. Just before I turned 13, the child welfare worker understood how critical my situation was, and she placed me in a school for girls, Our Lady of the Highlands in Fort Thomas, Kentucky. I never again lived with my family, and over the next few years, my mother had all of her children taken from her.

At Our Lady of the Highlands I did not have to fear physical or sexual abuse, but no matter how hard I tried, I could never be like the other girls. I was too slow making my bed, brushing my teeth, getting dressed; tasks we had to complete in firmly enforced time limits- and in complete silence.

The silence felt like a protective shroud. If I did not say what I thought or felt, it could not be used against me. In the three years that I was at Our Lady of the Highlands, I did not make a single friend. Of course, friendships were discouraged for fear of the girls forming homosexual attachments. We also could not talk about our lives or experiences before we came to the school. That was fine with me because I feared that if they knew what had happened to me; if they knew about the sexual abuse or the rape, then they might think I was worse than trash. I felt sullied, unclean and tarnished. How could anyone ever like or love me if they knew the truth?

After three years, I entered a foster home in Ohio. I was fifteen, and for the first time, I could be just another teenage girl. Next door lived the foster mother’s sister-in-law and her four children. Their daughter, Judy, whom I thought of as a cousin taught me how to dress, how to dance, how to laugh. We would sing to Martha and the Vandellas and other songs. The months chumming with Judy and her brother Randy were some of the fondest memories I have to this day. My happiness, however, was short lived. I danced with a black boy at the school homecoming dance and was suspended for a day while the school notified my guardians.

Right after that, I was awakened one morning by my foster father before anyone else was up and told to pack. He loaded me into his car and drove me back to the child welfare office in Newport. I was not permitted to say goodbye to anyone. My foster mother was ill, and I did most of the cleaning and cooking. I did everything they asked of me. Why? Was I impossible to love? To trust? I was devastated.

I was sent to live with friends of my mother and father in Pennsylvania. The wife, whom I will simply refer to as Aunt F, was never happy with me or with my sister, Marie, who also lived there. I no longer made straight A’s in school. I came straight home from school every day and Marie and I cleaned, washed, folded clothes, in short, did all of the housework for a family of five not including me and Marie. It was never enough, and Aunt F frequently grounded us for slight infractions of the rules. I lived with the family for two years, and that did not end well either.

I did have a boyfriend, a boy from my Aunt’s church. We were permitted to go to the movies twice a month with an early curfew, but once again, I did not have any friends. Friends got together after school or on weekends, visited each other in their homes, but I was not permitted that luxury. I had housework to do.

I was submissive, obedient and rarely complained. I feared that if I misbehaved, I would be put out again. My instinct was right. I lived with that family when my mother died.

On the day that my mother died June 1968, my sister and I were grief struck, and Marie did not want to eat dinner. Aunt F insisted that she eat, and Marie answered, “I don’t want to. I’m not hungry.” Aunt F slapped her across the face and screeched, “Don’t you ever talk back to me! Now do as you are told!”

I don’t know what came over me, but I jumped up from the table, grabbed Aunt F by the throat, lifted her off the floor and pinned her against the refrigerator. I did not raise my voice and said quietly but emphatically, “Her mother just died! If you ever touch my sister again, I will kill you!” In a surreal way, I can still picture her feet kicking frantically above the floor.

Uncle B calmed every down, and I was amazed that Aunt F and Uncle B did not punish me for what I had done. Aunt F avoided speaking to me for weeks, and when she did, it was to tell me that she was sending me to Indiana to live with my father. My father? The same man who had abused me?

That marked the end of my teenage years. When I arrived in Indiana, I had to quit school and get a job to help support my family. Marie came to Indiana too. Liz, my older sister, lived with my father already. She was pregnant and insisted that at five months, she was too sick from pregnancy to work. My dad earned $1.60 an hour, not enough to support a family of four, so it was up to me to get a job.

No school dances for me. No Martha and the Vandellas or Beatles. I worked until that arrangement too fell apart. These were my teenage years.

Karen, my friend of over 30 years, died May 1, 2017. Another hole in the fabric of my life. I can’t explain our relationship. Once, I was closer to her than to any person alive. She lived with me for three to four year stretches at a time. She would be here and then move out without warning. Sometimes she had a good reason. She bought herself a townhouse in Tampa, but she could not bring herself to tell me until three weeks before she moved out. Another time she moved to Springfield, Pennsylvania to live with her sister but a few years later, asked if she could come back when that didn’t work out.

Karen, my friend of over 30 years, died May 1, 2017. Another hole in the fabric of my life. I can’t explain our relationship. Once, I was closer to her than to any person alive. She lived with me for three to four year stretches at a time. She would be here and then move out without warning. Sometimes she had a good reason. She bought herself a townhouse in Tampa, but she could not bring herself to tell me until three weeks before she moved out. Another time she moved to Springfield, Pennsylvania to live with her sister but a few years later, asked if she could come back when that didn’t work out.