My family is rife with myths bordering on alternate realities. Some people might think the stories they repeat are lies. Until recently, I did too, but what is a lie? Anything that is not true, not factual? That is an over-simplification.

Take a look at the current political climate. People firmly believe in candidates and positions that are refuted by facts. Beliefs are not connected to truth, and when they are, it is almost by accident. We hold to facts that support our beliefs and dismiss all others. Families do that too, and family myths are as difficult to alter as religious beliefs. Take my own family, for example.

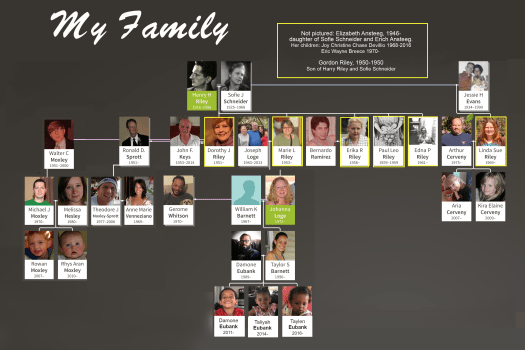

My father was an enigma. He was loving and affectionate. Were it not for him I would never have known love at all, and yet he abused me for most of my childhood. My father was a master at weaving myths into the fabric of our lives. His mother died when he was a toddler, and his father and grandparents raised him. He told us that his mother, a Cherokee Indian, was killed by an Indian man to whom she was promised in marriage. Of course, he told us that she was no common Indian maiden but a Cherokee princess. While I dismissed the princess part before I was an adult, he always insisted, and we always believed that she was Cherokee, or at the very least, half Cherokee by birth. That, we believed, is from whom my father inherited his high cheekbones and the slight hook in his nose. He told my mother the same thing, and she too believed that her husband was part Native American until the day she died.

When my younger sister, a dual national, had to declare her citizenship, she obtained a copy of my father’s birth certificate as part of her naturalization process. I was in my mid-thirties when I first saw this document and saw that his mother’s race was listed as ‘white.’ White? How was that possible? In 1916, no native American would be listed as ‘white’ on a birth or marriage certificate. My world dropped out from under me. A piece of my identity had been ripped from me and left me questioning everything I ever knew or believed about myself and my family.

You see, this was just another myth constructed by my father. He had two names and two birth dates and always used ‘Gordon’ as his middle name. After he had died, I learned that he never had a middle name at all, and his tombstone at the Veteran’s cemetery bears the wrong first name; the only name by which I knew him. He told countless myths, and my sisters and I used to laugh at most of them, but we never guessed that even his name and ethnic origins were constructive lies.

My mother was not given to spinning yarns, but my sisters were good at it. Heck, I spun a few of my own until I saw my father’s birth certificate. After that, I resolved never again to alter any fact in my life no matter how much the truth made me squirm. There are things that I will never tell a soul, but I will never knowingly lie. I came to believe that no truth could be as hurtful as the myths and lies I’d been told.

My oldest son’s father, my first husband, rivaled my father in confabulating alternate realities. Walter shared other characteristics with my father: he was affable and charming, and just like my father, he abused the ones he loved most. Walter had a quirk that my father did not. He was too insecure to share affections. It was as if he feared that to love someone else meant that person loved him less. For example, as proud as he was of his son, he accused me of loving our son more than I loved him and was jealous of the attention I paid our son.

I had grown accustomed to Walter’s many stories and learned to separate the myths from the facts by talking to his mother. After our divorce, I no longer cared about his self-aggrandizing stories but that is when they did the most harm. The combination of distorting truths and weaving tales of near mythical proportions, paired with his insecurities and his need to be loved more made him draw our son into his fictions. There were no versions in which he was not the victim of my malevolent deeds.

I learned later that Walter liked and praised me to others. He told them how smart and talented I was and valued the few pieces of my artwork that he kept after I left him. Nearly two decades and three wives after we parted, I saw floral arrangements and drawings in his house that I had made. How they survived his subsequent wives is puzzling, but there they were! It would seem that he reserved his rancor of me only to ensure his son’s love. To be more precise, that his son loved him more than he loved me.

Like my father and like his father, my son lives in a world filled with myths and inventions. In his confabulations, he was raised by his grandmother, and I had no time for him; I am the reason his father took drugs; I destroyed his life, and I did not love him as much as I loved his younger brother. Like his father, Michael feared that my love for my youngest son meant that I loved him less.

The myths within my family have done nothing except hurt us, and yet oddly enough, they are constructs meant to avoid pain. Until very recently, I thought of these myths as venomous lies and detested them. Then I had a eureka moment. Every person in my family who rewrites history and presents alternate facts is doing so to help them fill a painful gap or patch together pieces of their lives torn by tragedy and disappointment.

My father resorted to confabulation after her lover murdered his mother. In 1918, that was so scandalous and shameful that no one was allowed to talk about her in front of him. My father grew up with more questions than answers and resorted to creating his version of his mother, and ultimately his version of himself. His myths shaped his reality.

My sisters grew up with an abusive father, dire poverty and a mother who looked for solace in the bottom of a beer bottle. We were sent into foster homes and institutions, and everything about our lives was torn and sullied. This is not the childhood they describe to others. They will admit to our mother’s alcoholism and our destitute conditions as if they were but footnotes in their greater adventures.

My sons also knew trauma and rejection. My oldest son has his father’s ability to rewrite history and recreate reality to avoid inner conflict and pain. Most of Michael’s myths and distortions center around me, beginning with the lies his father told him. What is most interesting is how these myths and lies snowballed. They started with occasional hiccups in our relationship and culminated in a breach so wide neither of us can reach across anymore.

Back to my eureka moment. I now understand that every myth, every yarn is there to piece together a torn life. They are stitches and patches that make life endurable; that make it wearable. I wonder- if they deeply and honestly questioned themselves, could they admit that these are myths, or have they deluded themselves into believing they are truths? It also makes me wonder what myths I incorporated into my version of reality and what those myths might be.